One hour from Yangon (formerly Rangoon)

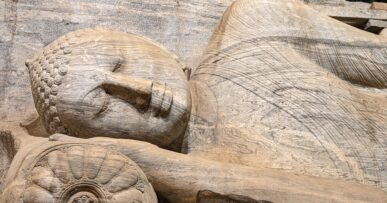

About one hour’s flight north of Burma’s major city of Yangon, lies the Bagan Archaeological Zone, where, almost one thousand years ago, the elite and the devout started building more than two thousand Buddhist pagodas, stupas, shrines and temples.

Bagan has much to commend it. It’s an easy distance from Yangon, its position on the Ayeyarwaddy River makes it a slipway to a relaxing overnight boat journey to Mandalay, and day excursions to the mountains offer novel activities and structures. Bagan is unquestionably spectacular, the pony and bullock carts are charming, its puppeteers and lacquerware artisans, are painstaking in their work and performances, and life moves at a gentle pace.

But it was in Bagan that I started to think that the Burma I was experiencing was “on show”, on stage, and that real insights into the culture and the people could be difficult to find.

Lacquer-ware Production : © Marjie CourtisThe archaeological zone

In an area around Bagan covering fifty square kilometres, there are still thousands of uniquely-Burmese curved, tapering, symmetrical and decorated brick structures. They stand in an aesthetically-pleasing array across the arid landscape, in hues of beige, ochre, orange and brown. Even the smallest pagodas and shrines have an intrinsic beauty.

Yet it’s the panoramic view of thousands of similar buildings spanning the horizon, disappearing into the distance, or out-reaching each other in height and size, that I found so stunning.

You soon learn that many of the original structures were toppled by an earthquake in the 1970s and that the government seized an opportunity in the 1990s to begin the “restoration” of the destroyed buildings, also forcing villagers from their homes among the ancient buildings.

Alas, UNESCO’s World Heritage Listers decry many of the restorations. Restoration must preserve not enhance the original buildings. So while the Burmese government wants to see this whole archaeological zone on the World Heritage List, current discussions and negotiations are likely to result in the listing of only a few buildings, artefacts and frescoes. The government has also scarred the landscape with a viewing tower and a new museum.

Nevertheless, the sites attract thousands of visitors each year.

The new sights of Bagan

Entrepreneurial Australians started the first ballooning company in Burma. Now there are two companies operating the flights, often booked out months in advance.

The morning balloon formations appear as a gently-choreographed performance, with individual balloons peeling away from the main flock of, say, sixteen balloons, to make their own pirouettes among the pagodas, temples and stupas.

The balloons have become so much a feature of the skyline at dawn and dusk, that they are no longer just a vehicle for spectators. They have become a spectacle in themselves. So while some visitors choose the entertainment value of viewing pagodas from the balloons, others choose the entertainment value of viewing the balloons from the pagodas.

Side trips from Bagan

A side-trip from Bagan to Mount Popo provides a different perspective on life in Burma. Mount Popo, at 1518 metres above sea level, is built on top of the lava plug of a former volcano. You climb 766 steps under a covered walkway to reach shrines paying homage to the Nat Spirits of an animist era, and to a lesser extent, to Buddha.

As with all religious locations in Burma, it’s obligatory to remove your shoes. During your barefoot climb you ward off monkeys seeking your water and food, pass men washing the steps with hand cloths, and pass ubiquitous clay pots providing potable water. Here tourists mix with pilgrims worshipping their gods, leaving offerings of the local currency, kyats, in glass-sided repositories or in bunches of bananas.

During the two-hour journey to Mount Popo I gained an impression of rural life, although most of the visible activities were concentrated in a specific area prepared for tourists. A buffalo in harness and covered in hundreds of baby flies, walked in a continuous circle, operating a mechanism which pounded peanuts into oil. The buffalo was an affectionate creature, willing to stop after one circumnavigation, to allow a neck embrace and a scratch.

The operators looked happy and so did those involved in making palm sugar, or jaggery. Most woman and girls had their faces decorated by thanaka, a beige-yellow paste from a tree of the same name, which is a moisturiser, a sunscreen and a decoration.

The day I bussed it up to Mount Popo, my group came on a novitiation ceremony, as young Buddhist made a commitment to Buddha by joining a monastery or nunnery, for the short or long term. Girls can opt to have their ears pierced instead! To find one of these ceremonies, listen for a cacophony of sound, possibly amplified from a megaphone and coming from drums, gongs and trumpets.

Or look for brightly decorated ponies carrying children dressed as princes or princesses, representing Buddha’s princely roots before he achieved enlightenment. A parade of people in longyis (a tunic-style garment worn by men and women) along the roadside carrying flowers or alms bowls, is also a good clue to one of these entrancing ceremonies.

A Cheroot-Smoking Tomato-Vendor : © Marjie Courtis

Remembering Bagan and Burma

If “all the world’s a stage” then this is no less so in Bagan. If you enjoy theatre, drama, colour and movement, Bagan is a good place to sample Burma. Whether you’ll get to the heart of Burma in Bagan, or really learn about Buddhism is another question.

Two puppets, a prince and princess, now hanging colourfully on my bedroom wall, remind me of the theatrical destination of Bagan, Burma. A little unreal, a little surreal but surely, overwhelmingly entertaining.

Beautiful Burmese Puppets : © Marjie Courtis