The former British capital of Rangoon

Schwedagon Pagoda –actually an extensive complex. Yangon © Marjie CourtisFirst impressions of Yangon

The official centre of Yangon (formerly Rangoon) is Sule Pagoda, as decreed by the British colonialists in the nineteenth century after they had demolished numerous other Buddhist symbols to build their version of the city.

From the balcony of my first hotel, I could see the imposing Shwedagon Pagoda in the distance, while overlooking the British-era Women’s Hospital, freshly painted in its original burnt red colours.

My first impressions of Yangon as a Buddhist city with a Colonial past endured during the seven-plus nights I spent in Yangon, between visits to the Golden Rock Pagoda, Inle Lake and Bagan.

Yangon’s Women’s Hospital © Marjie Courtis

The centre of Yangon

The exteriors of dilapidated buildings from the British era have peeling paint and plants sprouting from crevices. Some, like the former High Court, retain a British splendour. However its perpetual 12 o’clock time setting, and the coiled barbed wire around the perimeter, testified that this was an abandoned building. Its future is likely to be battled out by the Yangon Heritage Trust, the government and developers.

Former High Court Building – Yangon © Marjie CourtisThe Yangon Heritage Trust, located in the heart of the Colonial centre, is, an inspiring organisation determined to retain and restore the time capsule of the British era. The Trust’s walking tours present a narrative that brings the British past and the current development battles, into life, while looking to the future. For example, it has a vision for a landscaped Yangon riverfront for the city’s residents. Currently the Yangon River’s waterfront is largely hidden by roads, docks and buildings.

Opposite the Sule Pagoda is the MahaBanoola Garden Park, a peaceful people’s park, where people relax and children play. I saw one young boy poised on the edge of a fountain, saluting life with joyously raised arms.

Look at my world! Young boy at Mahabandoola Garden © Marjie CourtisMultiple lifestyles in Yangon

In Yangon, I saw a range of lifestyles. At one level was the lively street life, by day and by night. Men and women boiled oil or water on pavements and benches or burnt coals in braziers. They tossed delectable pancakes or rolled sliced betel nut into betel leaves sprinkled with lime and tobacco. People sold lottery tickets, cooked noodles, collected money for Buddhist seminars, and filleted fish. Rickshaw drivers awaited passengers.

Rickshaw driver awaiting passengers: Yangon © Marjie CourtisEating styles moved up a notch when I visited indoor cafes and restaurants. One morning, I followed a Burmese guest taking breakfast and figured out how to serve spicy Mohinga soup – a little broken chick pea cake in the bottom of the bowl, followed by ladles of the fish noodle soup, and then sprinklings of lime, fried onion, chopped chillies and fresh coriander leaves.

The next level in food styles comes with places like the colonial Strand Hotel where English afternoon tea is served to guests sitting in cane chairs, while musicians play the aung gauk (Burmese harp) and pattala (xylophone).

Less British, but similarly upmarket and touristy, you can find Monsoon restaurant also in the Colonial style, offering delectable dishes like fermented tea leaf salad. From Monsoon, it’s good to wander into the neighbouring not-for-profit shop, Pomelo, selling Burmese arts and crafts and using exotic shopping bags made of re-purposed newspaper. The exoticism of the shopping bags comes from the beautiful, circular Burmese script imprinted on the newspapers.

To experience upmarket and up-to-the-minute locations like the faux “speakeasy” called The Blind Tiger, I needed to call on my expatriate friends in Yangon – although I did later discover that a free booklet distributed in many hotels, gave reviews of places like this.

Happy street stall vendor in Yangon; © Marjie Courtis

Religion in Yangon

With eight-nine per cent of the population practising Buddhism, you inevitably encounter monks, dressed in various shades of purple and saffron, or devout nuns dressed exceptionally neatly in pink.

At Botataung Pagoda, the smaller number of tourists made it all the more enjoyable and friendly – the fewer the tourists, the warmer the smiles, and I could get closer to the many groups of percussion players.

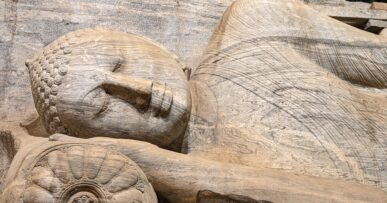

On a very grand scale, the Shwedagon Pagoda is full of devout pilgrims and beautiful symbols of Buddhism, from pagodas, stupas and Buddha images, to Bodhi trees and offerings of incense, flowers, candles, water and food. Here some of the sounds of music came from people striking bells to share the benefits of their good deeds with fellow Buddhists.

The Umbrella at Schwedagon Pagoda: Yangon © Marjie CourtisI saw synchronised teams of women walking in a line with a broom in each hand, sweeping the pagoda’s tiled pavement, on “their” day of the week – the day of the week you are born determines some aspects of how you practise Buddhism. The Pagoda had zones dedicated to a particular day of the week.

Schwedagon Pagoda is a colourful place, and all that glitters is often gold!

And there’s even more in Yangon

I kept finding things to do in Yangon. I took the circular railway from Yangon Central Station, running for several hours around the city. I didn’t see tourists on the train at all. It was a relaxing, journey and I had the chance for real personal interaction – warm smiles from a mother and her child, a gentleman wanting to practice his English, and people outside the train exchanging waves with me. The train ride gave an introduction to urban, suburban and semi-rural living.

Oh, by the way, kissing is forbidden in these train carriages!

No kissing on the Circular Railway – Yangon © Marjie Courtis

I visited Bogyoke Aung San Market, also known as Scott Market, a colourful, lively market full of gemstones, jewellery and handcrafts … and lots of people.

The traffic was heavy but there were bridges over the busiest ones. I learned to shadow Burmese pedestrians as they strode on to the road defying the cars and trucks. Yet there is no need to defy motorbikes – they are banned from Yangon’s streets.

At various points, I changed US dollars into Burmese kyats, avoiding the lower exchange rate for “no good” or “very old” notes, having obtained crisp notes in Melbourne, which I kept ironed!

Traffic in Yangon and the former Currency Department Building© Marjie CourtisYangon – a likeable place

Yangon is still Burma’s biggest city but is no longer the capital city. (The government moved it to Naypyidaw in 2006.) I didn’t run out of things to do or see. I saw determined people going about life as cheerfully as possible. It was a likeable place.

In Burma, I picked up undercurrents of poverty and oppression but it wasn’t overt. The population seemed resilient to me and I liked sharing their city.

I was especially happy in Yangon wandering around wearing necklaces of frangipani or jasmine flowers. Although sold as offerings to Buddha, I found their perfume a wonderful antidote to fumes, drainage smells, smoke, incense and ripe fruit. I enjoyed this city of sights, sounds, smells and tastes, whether I was strolling the streets, walking in the Colonial quarter or joining the pilgrims at a Buddhist place of worship. Future directions on the riverfront or in society, will be worth watching.

Schwedagon Pagoda – undergoing renovations © Marjie Courtis Percussionists at Botataung Pagoda, Yangon © Marjie Courtis