One May, I found myself cycling along the Canal du Midi with two friends. One was a French friend I’d accidentally met in Melbourne, the other an Aussie friend whose European cycling trip happened to coincide with my own trip to France.

It was a delightful way to meander through several hundred kilometres of Southern France.

But the Canal du Midi is more than a recreational zone for cyclists and boaters. It’s a World Heritage Listed oeuvre d’art (work of art), not only a hydraulic and structural engineering feat, but one of the worlds first designed landscapes.

The three of us were there to enjoy the cycling experience itself, but here we also had a journey that provided us with aesthetic charms and an engineering wonder.

The design and construction of the system of waterways, locks, aqueducts, bridges and tunnels, was fostered, in the seventeenth century, by Pierre-Paul Riquet, local farmer and tax-collector. It took several decades to complete and made the transport of wines and grains between the Atlantic and Mediterranean Oceans, much faster and much less hazardous than the route around Spain. It helped France enter the Industrial Era.

So nearly four centuries after its construction, we set off from Toulouse, with baguettes strapped to our vélos (bicycles), pedalling alongside canal boats with vélos strapped to their bows.

We spent 5 days covering the several hundred kilometres from Toulouse to Beziers, not quite to the Canals end point on the Mediterranean, which is at Sète. There were often plane trees lining our route, there were quaint lock-keepers cottages, vines, villages and intermittently green or red-poppied fields. And historic reminders at a commerative obelisk and on plaques.

The three of us had different cycling styles and mounts. Sarah had a typically French bicycle with no gears while Garis’s bike was custom-made at Cecil Walker Cycles in Melbourne. I settled for something in the middle, a Vélo Tout Terrain (mountain bike) that I bought from one of the Decathlon stores that are all over France.

Our little peloton of three worked as well as a newly-oiled bicycle chain along the tow path. We often outpaced the canal boats which had to navigate through more than seventy locks on the Canal, slowly climbing from sea level to 192 metres and then down again.

With our bicycle seats as vantage points, we would often look down on the canal boats with their red geranaiums, relaxed deck-settings, bicycles, ropes and flags.

We frequently stopped to watch at each écluse (lock) as they filled and emptied and the boats negotiated their way through. We could reflect that this Canal design, with its oval locks – minus six metres at each end, and ten metres in the middle – used structural designs and hydraulic systems, re-engineered from techniques from the Roman era.

If it was lunch time, the éclusiers (lock-keepers) had a scheduled break between 12.30 and 1.30 p.m. Not so bad for us, as we could just cycle on; but for the canal boats, a potential interruption to the flow.

Our approximate daily distance target was 60 to 70 kilometres. With a late start on the first day, we simply stopped when we were tired, and could see that the village of Villefranche-de-Lauragais was not too many kilometres away from the Canal path. As luck would have it, there was a town fair on that night to entertain us.

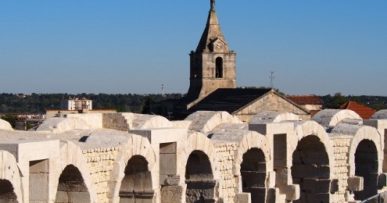

The path led us the next day to Castlenaudry, a beautiful marina and basin and a potential overnight stop. But with simply a lunch stop there, we cycled on, past the Malpas tunnel and on to Carcassonne. There we locked up our bikes up for two nights, so we could spend an entire day exploring its World Heritage Listed mediaeval ramparts.

Part of the reason for Carcassonne’s World Heritage listing is that it is a medieval fortified town with roots in pre-Roman times. But another reason is that it was restored in the 19th Century by Viollet-le-Duc. The restoration of Carcassonne has often been criticised as phoney, but that is not the real point. UNESCO points out the importance of both the positive and negative aspects of the restoration, as they have had a profound influence on subsequent developments in conservation principles and practice.

Carcassonne has a culinary heritage too. Castlenaudry, Carcassonne and Toulouse all claim title to the original, and best, version of cassoulet, a splendid winter stew. My French friend Sarah would not countenance the idea of a winter cassoulet in summer, especially one served in Carcassonne. Fortunately, she shared with me the recipe for Cassoulet from Toulouse.

On the walk through the lower, more modern Carcassonne to the higher, mediaeval fortresses, murals introduced us to the Cathars, a group sadly and brutally wiped out during the Spanish Inquisition.

We reached my favourite, and simpler, location on the Canal on the following night when we arrived at Le Somail. Now a delightful staging post for boats, it once served the same function for barge-operators, when the Canal was a trade route.

Finally we reached Beziers, where six locks in rapid succession provided a watery staircase towards sea level, a climactic finish to my serendipitous vélo-tour along the Canal’s tow path.

Whether you experience it from the the Canal’s tow path. or first-hand from a canal-boat I can recommend that you go with the flow along the Canal du Midi.