Boating activity on Inle Lake, Burma : © Marjie Courtis

Inle Lake – Not quite Venice

Inle Lake in Burma (Myanmar) is no Venice, but it shares Venice’s proliferation of canals. Rather than grand buildings built by Renaissance merchants, simple stilt houses are built over the water by the local Intha people.

I was on tour in Burma and arrived at Inle Lake with great anticipation, a new world of water, contrasting not only with Venice but also with Burma’s Bagan or Yangon or Mandalay.

I toured Inle Lake and its adjoining canals in a motorised long-boat. It sped down the canal from the town of Nyaungshwe, halting abruptly at the lake’s entrance. Here I watched agile Intha men, adeptly using their feet to swivel the conical fishing net into various positions.

Intha fishermen on Inle Lake : © Marjie Courtis

The impressiveness of the spectacle was somewhat diminished when I learned that that this fishing method is no longer used. It’s been replaced by a new method which involves thrashing the water to drive fish into a net further down the lake. So what I was witnessing was not a cultural reality, but indeed, a performance, albeit a colourful one.

Meditative “time-out” on Inle Lake

My day on the long boat was meditative and relaxing. It seemed poetic to be slipping along one of the canals of in the long boat pushing through the water hyacinths. I’d been reading George Orwell’s novel “Burmese Days” and felt I shared a similar experience to him, passing the “water hyacinth with profuse spongy foliage and blue flowers”.

My guide gave a new perspective when he demonstrated the importance of water hyacinths to the Intha people who are using them to help reclaim land from the lake. The water hyacinths provided one layer of spongy solidity, augmented by a layer of weed from the bottom of the lake, and a third of mud.

These layers form the bed of their floating gardens, which are anchored by long bamboo poles to the bottom of the lake.

The men row or guide their own non-motorised boats with their feet. Men and women farm their floating gardens from boats and vendors use them to come alongside the touristy long-boats.

Intha enterprises flourish around the lake or beside the canals. The long boat took me to places where products – from the decorative to the utilitarian — were being manufactured. I saw silver jewellery being made, cigar-sized cheroots being rolled in lotus leaves and flavoured with betel nut, boats being built and fibres being woven.

Bright silk yarn was being woven into longyi, the wrap typically worn by men and women. Even more intriguing was the weaving of the internal fibre from the lotus stems. So fine is this strand of fibre, that the fabric for Buddhist’s monk’s robe would require one hundred and twenty thousand of these stems!

On Inle Lake we met women and girls of the Paduang clan, the older women wearing the traditional twenty four brass neck rings, once designed to protect them from big cats, now simply a decoration. They were friendly woman, playing guitar, weaving, or posing for photos. But unlike the Intha, these people were literally out-of-place, as they’d become employees – or perhaps indentured labour – brought here for the tourists.

A woman of the Paduang clan : © Marjie CourtisBeyond Inle Lake

Further afield, I discovered the more mainstream ethnic grouping of the Shan people. By land, I visited a teak monastery in Nyaungshwe, where an adjacent man-made cavern was host to a myriad small red Buddhist images, each in its own small alcove. Names from around the globe adorned individual images, since a tiny donation is all that is needed to make you a “sponsor”

I dropped in on an umbrella-making establishment where the rainproof layer was made from the paper of mulberry bushes. I sipped an enjoyable shiraz as I watched the sun set at Red Mountain Winery near Inle Lake.

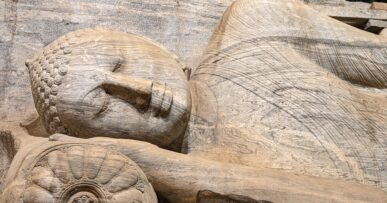

The Pindaya Caves, an hour away, were particularly beautiful, being home to 8000 gilded Buddha images. The carvings lined the narrow meandering walkways, and adorned the cave walls, rising above one other and contrasting strangely with the naturally-formed stalactites.

Buddha images & stalactites – Pindaya Caves : © Marjie Courtis

Buddhism at Inle Lake

At Inle Lake, there were more Buddhist shrines and temples, though was less of a focus at Inle Lake itself.

There was a cluster of stuccoed Shan pagodas at Ywama. In another part of the lake was the Phaung Daw U Pagoda, where so much gold leaf had been randomly affixed to its Buddha images, that they had ceased to look like Buddha images, and looked more like golden snowmen.

Had I been there in September or October, I would have seen these revered golden images sail from village to village on a huge barge, paddled by Intha, as part of the Golden Bird Festival.

Pagodas near Inle Lake : © Marjie CourtisPhotogenic and Productive

Photographs and souvenirs remind me of this beautiful location in Eastern Burma. I enjoy my decorative red umbrella and my handwoven scarf, painstakingly woven from silk and lotus fibre at Inle Lake. If it had been made entirely of lotus fibre, it would have used up 7000 stems!

The simple, dogged productivity of the people around Inle Lake, is one of my most lasting memories. I remember their enterprising transformation of the local vegetation into functional or decorative objects. There was the bamboo, used as both a building material and anchor. There was the creative use of water hyacinths and mulberry leaves, and the application of the lotus stems to luxurious textiles. And Inle Lake was such a tranquil place, even when people were hard at work!

Umbrella-making with mulberry leaves : © Marjie Courtis