Evita lives on in Buenos Aires

Although I visited Argentina with more interest in tango and trekking than politics and Eva Perón, she was hard to avoid in the capital city of Buenos Aires. She seemed to be following me around whether I was at the San Telmo Sunday market, walking or bar-hopping in the up-market neighbourhoods of Palermo or Recoleta, mingling in the public spaces of Monserrat, having a simple conversation or paying a bill using the new ten peso note with her image on it.

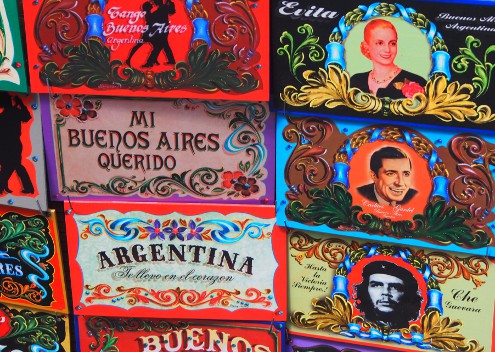

Evita in Fileteado at San Telmo Market © Marjie CourtisWhether I wanted to hear her story or not, throughout Buenos Aires, there it was. Evita, as she was affectionately known by the populace, arrived in Buenos Aires as an aspiring actress in the 1930s as an illegitimate daughter of Juan Duarte. She had some radio and film success before beginning her rise to fame ten years later, as the mistress and wife of sometime president Juan Perón. As a charismatic champion of the poor and powerless, her death in 1952 left many Porteños (residents of the port city of Buenos Aires), so grief-stricken that the Plaza del Mayo, in front of the Presidential Palace in Monserrat, was full of mourners for at least four days.

Despite her admirers, Eva has had many detractors, having been seen to have abused her political power and personal prestige. I tried not to take sides.

My guide Hernán first took me to Monserrat and showed me the Presidential Palace, where Juan and Eva Perón frequently addressed hundreds of thousands of citizens from the balcony. The Palace is also known as the Casa Rosada (Pink House) because of the pink hue dating back to the nineteenth century when it was painted with a mixture of lime and oxblood.

The Plaza del Mayo in front of Casa Rosada has always been a political hub, and is now home to numerous temporary and decades-long protests against the government. The Mothers of the Disappeared keep up a melancholy vigil in symbols and in person for the victims of torture from the military regime of the 1976 to 1983. The families of military personnel have a “tent embassy” demanding compensation for their losses during the Islas Malvinas war (the “Falkland Islands” to the British.) And a shabby barrier erected around the Casa Rosada showed the government’s concern about more protests.

Interior of Eva Peron Museum © Marjie Courtis

The next day Hernán took me walking in Palermo and though there were many stops, one was the Eva Perón Museum. The museum purports to present both the positive and negative views of Eva. However, because it’s run by the Eva Perón Foundation, it pays to be open to possible bias, while reviewing its exhibits of clothing, film, photos, radio presentations and other artefacts.

The grand nineteenth century mansion that houses the museum was acquired by the Eva Perón Foundation in the 1940s to house the poor and homeless. So the museum is worth visiting simply as a testament to the social disadvantage of the 1940s and 1950s and the fine living enjoyed by the privileged classes before that time.

During my visit, Hernán told me a story about his grandfather that was perhaps even more interesting than the museum exhibits. As a young boy in 1951, his grandfather had waited in line three times to speak to Evita because he was supporting his mother and siblings by delivering newspapers. When he finally was received by her, he told her that he could support his family better if he had a bicycle, because he could deliver more newspapers in the same amount of time. So she wrote a letter, or perhaps a decree, to a bike shop requiring them to provide one. Her methods were sometimes questionable but Evita made all the difference to Hernán’s family.

Conversations with Porteños kept bringing her up. For example, they were appalled by the fact that Madonna, not an Argentinian, starred in the film version of Evita, and that Madonna had the apparent arrogance to stand on a higher balcony than Evita had used when she visited the Casa Rosada.

The next day, Hernán’s associate Mily, took me around Recoleta cemetery. The excitement about her leading my visit was that Mily’s family owns a mausoleum there, and we were going to have the rare opportunity to visit its interior, on both the ground and lower levels. I learned of the burden and privilege of being a modern-day mausoleum owner.

With Mily’s commentary in the cemetery I discovered the first art nouveau sculpture in Argentina, a couple whose bronze busts appear back to back, apparently to reflect the true nature of their marriage; and a number of mausoleums and crypts in various stages of repair and disrepair.

But you guessed it, Mily’s private tour included a visit to the façade of the Douarte family mausoleum where Evita was finally buried with that family’s permission, several decades after her death.

Eva Peron’s Final Resting Place © Marjie CourtisA few days later, having a cocktail at the Melia Recoleta Plaza Boutique Hotel, barman Dele, presented an elegant brochure describing Evita’s links with the hotel. She had lived in an apartment in the building before she met Juan Perón and seamstresses who made some of her dresses, worked in a room now incorporated into the hotel. And her husband, Juan Perón, had been arrested here before imprisonment between several terms as President. The re-furbished building has an olde-worlde feel and if Dele is on duty, you can be assured of a first class cocktail.

And in more neighbourhoods she’d be there again. In the famous San Telmo market she appeared on numerous souvenir plaques adorned with the uniquely-Argentinian fileteado artwork.

I eventually did find the tango and trekking in Argentina, but in the meantime, I couldn’t help being haunted by Evita.

You may or may not choose to deliberately include Eva Peron sites in your tour of Buenos Aires. But, love her or loathe her, you can’t visit Buenos Aires without encountering the ghost of Evita.